Secluded within the confines of a large steel factory, circled by endless fields of snow and hidden behind a dilapidated wall, stands a tiny Jewish cemetery. A narrow path, a trail through thick snow, leads to a rusted wrought-iron gate. It is shut; its padlock corroded, but nearby, in the wall, there is a hole, and a trail of fresh footprints continues there.

Secluded within the confines of a large steel factory, circled by endless fields of snow and hidden behind a dilapidated wall, stands a tiny Jewish cemetery. A narrow path, a trail through thick snow, leads to a rusted wrought-iron gate. It is shut; its padlock corroded, but nearby, in the wall, there is a hole, and a trail of fresh footprints continues there.

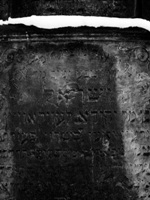

The place is charming; irregular rows of crooked headstones covered in Hebrew inscriptions are entangled in wild ivy. This cemetery, no more than a handful of graves, is perhaps the last testimony of the Judaic community that thrived here in Częstochowa, as much as in the rest of Southern Poland, from as early as the 17th century.

| This community no longer exists, though once it enjoyed a period of acceptance as well as economic and cultural prosperity. Here was once in fact a synagogue, and later two, a Jewish

market and a district hosting a modest, yet significant population of Jews. In an interview with Plater Robinson of Tulane University in Louisiana, Leo Scher, a Holocaust survivor, describes his native prewar Częstochowa: „A beautiful people. Everybody was happy, everybody was poor but happy. Average person was satisfied. This is it. People were living that way for hundred of years. One was dressed well, one was dressed a little less well. One was dressed nice beautiful new suit, coat and tie, a little hat. But everybody was happy.” And he adds later „everybody was happy, going to work. People who didn’t work were happy. Even the beggars were happy. Because when they begged they got what people gave what they needed, and they were happy.”

Then the Second World War came. A ghetto was set up, sealed first and then emptied. Auschwitz is just an hour’s journey away, so day by day, train by train everything changed. The synagogue, once a jewel of the Jewish quarter an impressive structure with a study room and a rich library housing a rare collection of the most sacred books, was burnt to the ground in a pogrom launched by the Nazis. Other parts of the historic quarter went up in flames too (their tenants murdered, so did retirement homes and orphanages, while the few buildings left were used as storage for plundered goods. The war ended sixty years ago, and Auschwitz is no more; it was liberated by the Red Army in 1945. There is little left of Treblinka-Birkenau save for a solitary wood, Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen are now busy, industrial towns with factories, cinemas and schools, but the war and the genocide left a terrible wound in our minds and in our hearts, and this wound may never heal, in fact, it is still fresh and throbbing. But as I stroll through a copse, here in this cemetery, and later through a thick bush; as I stride at times through deep snow, for it is January, a different reflection forces itself upon my mind and it calls for a different memory, a recollection of different times. Here reigns undisturbed peace, silence that is unspoiled, an aura of innocence. Many similar cemeteries witnessed to scenes of mass murder, crimes committed on the weak and defenceless, and yet here the war left little trace; that past is not, it seems, this graveyard’s past. All tombs date back to the times long preceding the war and only the emptiness, the space between one stone and the other, speak subtly on the broken thread: there were dead and then there were no more dead. Thousands of Jews, men, women and children from Częstochowa, a quarter of the city’s entire population, along with other Jews from the surrounding areas, died in concentration camps in Auschwitz and Treblinka-Birkenau, with Poles, Russians, Gypsies and others – homosexuals and the handicapped. Some died in a death march to another camp – the final irony – merely few days before the war’s end. This city’s entire Jewish community was exterminated, save for a group of five to eight hundred who returned here after the war in 1946, and some earlier in 1945, to look in vain for their homes which had been burnt and reduced to piles of debris

One such person was Abraham Bomba (originally from Częstochowa), the Treblinka barber from Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 documentary Shoah. He, too, returned here briefly, to find but conflagration, a ruined town, and no signs of Jewish life. The city was gone; there no longer was a synagogue (though at one time there were two), there was no Jewish market, and nothing remained of a once prosperous district. He consequently left for New York, and later, when he retired, moved to Israel. In a shabby area, hardly a neighbourhood, live now the poorest of modern Częstochowa: the unemployed, the evicted, the troubled and plagued, just like their homes, by neglect and condemned to marginalization and oblivion. All in all, save for sporadic traces of distinct Judaic architecture – arched passageways, tiny courtyards, dark, steep and narrow staircases – there is little left of once a Jewish district. Still, there is this cemetery, and protected from time by its seclusion – the vast steel mill on one side and endless fields on the other, a wall, a wrought-iron gate with a corroded padlock – through a hole caused by eroded bricks, it allows a glimpse of a once happy past.

Once more I look at the dates, clear the snow if I must; after all it is winter and it snowed all night: Birnbaum Elke died in 1886, Chaim Adler died in 1912 leaving behind his bereaved wife and two adult children, Gelbwachs Mania died in 1928, I read and realize that these dates speak of better, happier memories, times long preceding the war, the holocaust, the nightmare. These people died unaware and rest in undisturbed peace; their silence is innocent and this place, with their graves, is their garden – the garden of the fortunate dead, 'And the dead know nothing (Ecclesiastes, 9:5).’

Though educated in Canada, the UK and Italy, Piotr grew up in Czestochowa |